Bad Laws

TIGER LEGISLATION – A SHORT HISTORY

Agency: U.S. Department of Interior

1970

- The Animal Welfare Act of 1966 was amended to include all warm-blooded animals (tigers now covered) used in exhibition or sold as pets. Coverage expanded to animal exhibitors (i.e. circuses, zoos and roadside shows).

- US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) delegates standards and enforcement of the Act to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) who issue the Exhibitors License. This license legitimized backyard breeding and has probably caused more tigers to die than all the poachers in China.

1973

- Endangered Species Act of 1973 enacted to prevent the extinction of wildlife and plants. It basically said that any US citizen had to get a permit to do anything with endangered species: import, export, take (meaning harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect), or engage in interstate or foreign commerce.

1979

- Captive-Bred Wildlife (CBW) regulations allow prohibited activities for non-native endangered species born in captivity in the US which enhance the survival of the species.

- Registration with the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is required to get CBW permit.

- Registrants required to maintain written records, and report annually to FWS – for live animals only.

- There were no activities permitted for dead animals, in order to prevent breeding endangered species for illegal trade.

1993

- Amendment to CBW regulations eliminated education through exhibiting captive bred wildlife as the sole justification for issuing a CBW permit (unfortunately it was not enforced). FWS concerned that CBW regulations were drifting from the original intent to “encourage responsible breeding that is specifically designed to help conserve the species involved.”

1998 – September 11, a bad day for tigers

- Amendment to CBW regulations deletes the requirements for CBW registration or annual reporting for holders of Generic Tigers (this is the generic tiger loophole) and applies only to tigers.

- Justification for amendment: “It is estimated that the paperwork burden of the CBW system and the public will be reduced:” The Service recognizes the rule will have a beneficial effect on a substantial number (400) of small entities, such as zoos, circuses, or independent breeders.

2011

- Proposed removal of Generic Tiger Loophole because of concern for deteriorating conservation status of wild tigers.

- Lack of registration and reporting seen as potential contributor to illegal trade.

- Comment period got 15,127 public responses, mostly in favor of removing the loophole.

- Comments arguing against the removal are from breeders, exhibitors, private owners and participants in the exotic pet trade.

So What Has Been Accomplished?

The combination of the USDA giving away licenses and FWS deleting generic tigers from reporting requirements accelerated the breeding binge that began in the 1980s and continues to this day. The supply of cheap, unregulated tigers to exhibitors is the primary reason we have more tigers in this country than exist in the wild in the rest of the world.

So What Can We Do?

Strengthen and enforce existing laws and enact new legislation to end the unregulated breeding.

Although focused on tigers, they should be considered a surrogate for all the big cat captive bred species. The 6 big cat species (tigers, lions, leopards, cougars, cheetahs, and jaguars) will all benefit from Big Cat Legislation.

At the moment there are a number of Big Cat initiatives, some federal and some state level. And while there are a number of talented and dedicated people and organizations involved, a consolidated plan has yet to emerge.

Some of the initiatives are:

- Request USDA licensed facilities to report tiger inventory and transactions annually and make it available for public review.

- There is a 4 week petting window for tiger cubs. This allows public interaction with tiger cubs between 8 and 12 weeks old. Close it.

- Establish standards for big cat enclosure size, food and vet care.

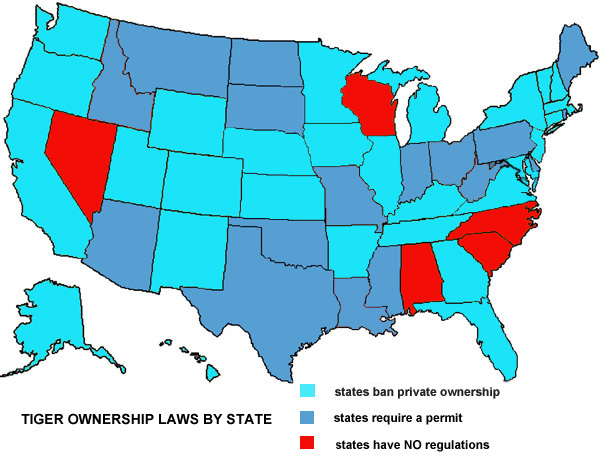

- Pass laws in the five states that have no laws at all.

- Eliminate the Federal exhibitors exemption in state laws.

- Prohibit trade in trophy parts.

We urge support these and other initiatives that will end the unregulated breeding, irresponsible ownership, public interaction and commercial exploitation. We believe we can put an end to the abuse, suffering and premature death of tigers and other big cats.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – A Short History*

The 1970s were golden years for the USFWS Office of Law Enforcement (OLE). Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972, followed by the Endangered Species Act in 1973.

Newly appointed chief Clark Bavin, known as the J. Edgar Hoover of FWS, began to turn old-time game wardens into professional special agents. Wildlife agents found themselves shipped off to Glynco, Georgia, to receive fifteen weeks of intensive training in criminal investigations, firearms, self-defense, and wildlife law. It was their final evolution from duck cops into a new breed of investigators.

By 1977, an all-time high of 220 special agents, trained in the mode of the FBI, successfully broke the back of the illegal alligator trade. The timing couldn’t have been better. The exploitation of wildlife was rapidly rising as word traveled of the quick and easy money to be made.

The agents of OLE felt a heady confidence about taking on the challenge as protectors of America’s wildlife. They were now federal agents investigating premeditated and well-organized criminal acts that just happened to involve animals. Their numbers were growing and FWS appeared to be solidly behind their work. They couldn’t have been more wrong. Though their mission remained the same, it would all be downhill from there.

FWS is primarily known as a biological-research agency responsible for protecting wildlife and its habitats. In a government body mainly composed of managers and biologists, OLE is forever getting a smaller piece of the pie. The number of their agents slowly dwindles, while their investigative caseload continues to grow. These days OLE has 195 special agents. That’s down from 220 thirty-five years ago. Take away the number of supervisory people and there are probably only about 130 field agents in total. And fewer than 20 of them do any high-level undercover work. By comparison, the FBI has 12,000 special agents. Yet global wildlife crime ranks just behind drugs and human trafficking in terms of profit.

*courtesy Jessica Speart in Winged Obsession

The FWS budget for fiscal year 2016 is $2.9 billion.

The Office of Law Enforcement’s budget is $75 million.

The Multinational Species Conservation Fund budget is $11 million.

There is an 11 percent Federal excise tax on guns and ammunition and a 10 percent tax on handguns. These funds are collected from the gun manufacturers by the Department of the Treasury and are apportioned each year to the States by the Department of the Interior.

In 2015 this amounted to __

Amount spent on the captive bred wildlife problem is $0